UNC GI Conference with Dr. Drossman: Getting Better

Written by Douglas A. Drossman, MD and Jennie Rambo

Over forty years ago, when I was completing my GI fellowship, I put together a series of luncheon meetings for GI faculty and fellows at UNC Medical Center where we could meet to discuss treatment options for our more difficult and complicated clinical cases. This meeting has continued every month throughout my tenure on the GI faculty at UNC and now while I am in private practice. While the format and topics of discussion have changed over the decades, we always use this time to sort out how to make things better for our patients. Sometimes we have case discussions with the patient in attendance, show videos or have role play and case discussion. Usually we see patients who are struggling with difficult clinical issues and our task is to find solutions for them. Last year, for one of these meetings, I thought it would be valuable to have our group interview patients who were doing well. It would be a different perspective by understanding through their eyes what made things better. I asked three patients of mine to come speak about their experiences of illness and recovery. I’d like to share my thoughts on a few common themes in their care as well as why I think they got better.

Like most of my patients, these three women came to me hopeless, frustrated, and suffering from DGBI that controlled their life. As they told their stories, it was evident that they were not able to function in their daily lives. One patient, Kim, required help to get through daily tasks like getting out of bed and bathing. As her condition deteriorated, she became resigned to thinking this was an unalterable condition of her life.

After reviewing the patients’ files and seeing them for the first visit, I felt confident that I could suggest some changes in both medications and lifestyle. In the months and years that followed, they got better. Although the changes I suggested were a part of their recovery, what contributed most was that each of these patients engaged in the idea that they could improve and took responsibility to accomplish that. The belief in recovery brought about the change. This may sound a bit like Dumbo the Elephant believing he could only fly with the magic feather, but there is a scientific basis for this phenomenon.

Being Heard

If you watch the video, each of the patients describes what it felt like to be told by other doctors there was no cause for their symptoms and the problem was “all in their head.” They also describe the relief to be, as one of the patients put it, “listened to and heard.” There is a logic behind this– what rational patient would follow a doctor’s recommendation when they feel the doctor doesn’t even understand the symptoms?

Recent research, both my own and that of my colleagues, quantify the positive outcomes that result from a strong patient-provider relationship, and the findings overwhelmingly support the importance of listening to improve clinical outcomes. Yet, according to one study, the average time patients speak before being interrupted by providers is 22 seconds![1] The evidence proves that an engaged patient who trusts their doctor has reduced symptom severity, less emotional distress, and improved satisfaction and coping skills.[2] And fundamental to engagement and trust is the feeling of being heard.

Understanding the Illness

Another important aspect of reversing the course of illness is understanding the illness itself. Patients who understand what their diagnosis is and why this illness is affecting them can make informed decisions with their doctors on which treatments might work best in their situation. Studies show that for the DGBI like our patients had, doctors do not clearly make a diagnosis and explain the reasons for their symptoms. This is in sharp contrast to patient’s with structural diseases like ulcerative colitis or pancreatitis[3]. Notice in the videos how each patient used their understanding to effect positive change. For Kim, understanding neurogenesis gave her hope that she could in fact change the course of her illness, and motivated her to make lifestyle changes that increased the effectiveness of other treatments. Karen understood the value of CBT (Cognitive Behavioral Therapy) and benefited as it helped her to examine behaviors that were negatively impacting her health. Leslie attributes her recovery to learning about the connection between a traumatic experience and her symptoms.

For patients who have had multiple negative tests and symptoms without cause, or have been told the pain is “all in their head,” learning about DGBI can alleviate anxiety about the unknowns of their condition. For example, a patient with abdominal pain, worried that the pain she feels is caused by some horrible disease that just hasn’t been found yet, might be reluctant to try therapies directed at the brain. However, once understanding that the brain and the gut are hardwired, and a dysregulation between the brain and gut can cause hyper sensitivity to pain, the patient may make the choice with her doctor to stop treating the pain with opioids, and instead focus on treatments like CBT, neuromodulators, and hypnotherapy, which can eventually “rewire” the brain back toward normality. For more information on the brain-gut interaction, click here to download a free diagram with explanatory video link at https://romedross.video/Brain-GutAxis

Making Changes

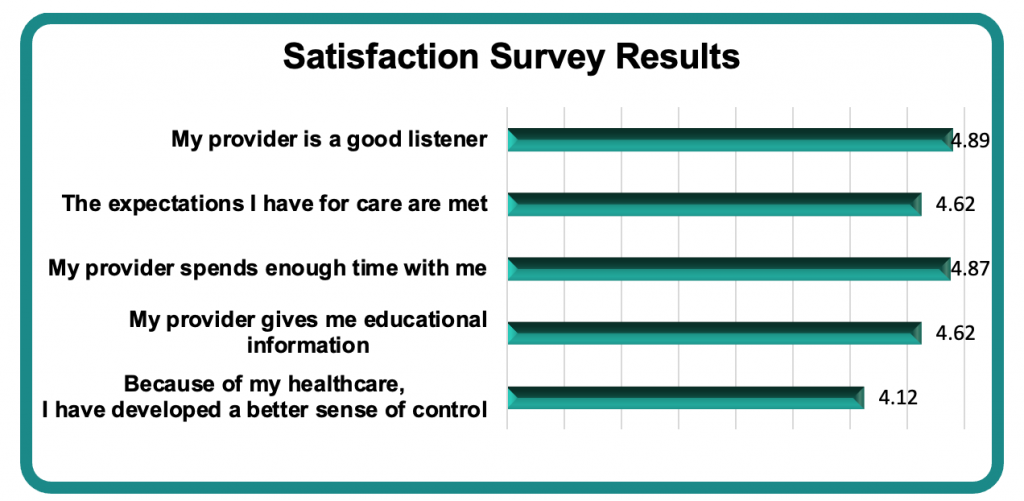

The survey below of patients in my practice shows how the provider’s care can impact on patient satisfaction when he listens, spends the needed time, and educates them on their conditions. This can lead to the patient achieving a better sense of control because of the provider’s care.

1 – Strongly Disagree

2 – Disagree

3 – Neither Disagree nor Agree

4 – Agree

5 – Strongly Agree

These 3 patients got better because first, I listened to them, engendering their trust, which then opened the possibility that they could get better. I took care to ensure they had a thorough understanding of the rationale behind the course of treatment I recommended. All three agreed to make changes in several areas, and the more they directed these changes, the more control they regained over their illness.

[1] Marvel MK, Epstein RM, Flowers K, Beckman HB. Soliciting the Patient’s Agenda: Have We Improved? JAMA.1999;281(3):283–287. doi:10.1001/jama.281.3.283

[2]Drossman DA, Ruddy J. Communication skills in disorders of gut-brain interaction. Neurogastroenterology LATAM Reviews 2019;2:1-14.

[3] Linedale EC, Chur-Hansen A, Mikocka-Walus A, Gibson PR, Andrews JM. Uncertain Diagnostic Language Affects Further Studies, Endoscopies, and Repeat Consultations for Patients With Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 Dec;14(12):1735-1741.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.06.030. Epub 2016 Jul 9. PMID: 27404968.

5826 Fayetteville Rd., Suite 201 Durham, NC 27713

5826 Fayetteville Rd., Suite 201 Durham, NC 27713  (919) 246-5611

(919) 246-5611