Stigma in DGBI & Clinician Burnout: Leveraging the Patient-Physician Relationship to Heal Patients and Doctors

Written by Jordyn Feingold, MD, MSCR, MAPP

Jordyn Feingold, MD, MSCR, MAPP

You’ve all likely heard the following philosophical thought experiment regarding the phenomena of observation and perception: “If a tree falls in a forest, and no one’s there to hear it, does it make a sound?”

I pose a related question about the matter at hand, stigma in disorders of gut-brain interaction (DGBI):

“If a patient’s bowel causes debilitating symptoms, but their doctor can’t find inflammation or structural abnormality, is anything even wrong?”

I hope you already know that the answer is a resounding YES; indeed, likely both our patient and doctor are in need of some healing. However, even in 2021, many physicians do not acknowledge the legitimacy of these disorders, historically termed “functional” or “psychosomatic.” Even this terminology, and the implication that these diseases are at best purely psychological, or at worst, simply made up, carry a great deal of stigma that may be perpetuated by the health care system and subsequently internalized by patients. Accordingly, the terms “disorders of gut-brain interaction” or “biopsychosocial,” which are more accurate and scientifically based have replaced the antiquated, though still ubiquitous, terminology.

As a recent medical school graduate, future psychiatrist, and clinician well-being & burnout researcher, I have come to appreciate firsthand the complex dynamics within our health care system that contribute to this state of affairs. Here, I hope to provide a history and some suggestions on moving us forward in acknowledging and treating these very real illnesses.

In the mid-seventeenth century, Rene Descartes unleashed ‘Mind-Body Dualism’ on Europe and the world, postulating that the mind and body were distinct and separate entities, and henceforth, the human body could be dissected without consequence for the human soul. Ushering in a new wave of biomedicine based in visible morphology, this paradigm set in motion the basis of our modern health care system, one that relies heavily on lab tests, biomarkers, histology, and pathology. According to this model, “real” medical problems are those observable phenomena, diagnosed and legitimized by visible evidence of disease.

Well, enter disorders like DGBI, which include the 33 adult and 20 pediatric conditions, which inherently lack evidence of their own existence, without biomarkers or visible structural abnormalities to prove that they are real. With Descartes’ legacy very much alive, these disorders remain elusive, barely touched upon in medical education and training, their diagnoses fraught. So, what happens when patients with DGBI or other functional disorders show up in a physician’s office?

While a solid clinical history, the use of Rome symptom-based criteria, and the absence of ‘red flag’ symptoms can typically make a diagnosis of DGBI, the average physician without adequate education or experience in treating these conditions might insist that patients receive a “million-dollar workup” (think lab tests and imaging to start). Physicians may do so out of justified fear of being sued or missing a “scary” diagnosis (e.g. cancer, inflammatory bowel disease). So, when

tests come back ‘negative’ (“great news – no cancer for you, ma’am!”) patients may be—tacitly or more explicitly— told by their—likely overworked—physicians that there is “nothing wrong” with them… Perhaps what they are experiencing is “in their heads,” or simply a “product of stress.”

[Let’s pause here to remind our readers that approximately 50% of physicians are experiencing symptoms of burnout—another invisible syndrome of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and low sense of personal efficacy related to their work. Drivers are burnout include heightened demands on physician’s productivity, less face-to-face time with patients, fee-for-service payment structures, immense documentation burdens, and myriad systemic factors that undermine doctor’s abilities to be fully present with their patients.]Thought Experiment:

- Imagine you are physician experiencing burnout who has fifteen minutes to see a patient who walks in with severe physical complaints, but their workup showed no evidence of disease … What thoughts emotions, and physical sensations are you experiencing as you sit with this patient and review their chart? How will you spend this fifteen-minute visit?

- Next, take a moment to think about how you might react differently with this patient in the same amount of time if the patient’s workup came back positive for a visible structural abnormality or evidence of inflammation. What thoughts emotions, and physical sensations are you experiencing as you sit with this patient and review their chart? (Consider: might you be more willing to spend a few extra minutes because you see their diagnosis as “legitimate?” Are you less stressed because you know what you need to do to treat their disease?)

For patients, upon receiving news of the negative work-up, some patients may be perhaps partially reassured, but still many are also highly dissatisfied by this mismatch between their symptoms and these clinical findings. In fact, it is not unusual to hear patients say something along the lines of: “I would have rather the tests just showed cancer…. At least then I’d know what’s wrong.” Indeed, in the paradigm of mind-body dualism, receiving a structural diagnosis is validating and offloads the distress of thinking that what the patient is experiencing is psychiatric!

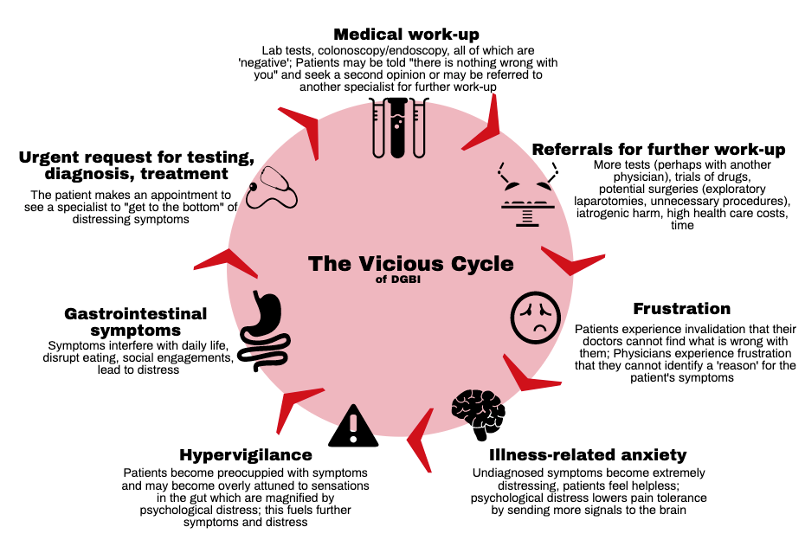

Without such validation, patients may request more tests, even exploratory surgeries to help identify a reason that they are living in daily agony. Physicians may comply, or frequently, refer the patient to a colleague who might pick up on something they may have missed. All of this— the frustration on the part of the physician who has not “found anything,” the lack of a unifying or concrete diagnosis, and the chronic invalidation these patients experience from the health care system—create a perfect storm of stigma and frustration for all parties.

What’s worse is that patients may develop illness-related anxiety and hypervigilance associated with their symptoms, worsening their clinical picture and quality of life. These patients may then come across as more “demanding” or “difficult,” creating a further chasm in the doctor-patient relationship – a relationship that is at the core of both DGBI and ameliorating physician burnout.

Figure 1: This image [originally published in Neurogastroenterology & Motility (Feingold & Drossman, 2021]) demonstrates the “vicious cycle” experienced by patients with DGBI.

So, how do we break this vicious cycle and intervene on two highly related, stigma-prone conditions: functional disorders (like DGBI) and clinician burnout?

- Education & Training. Doctors in training must learn about DGBI and functional disorders as legitimate diagnoses, and understand their mechanisms, diagnostic criteria, and evidence-based treatments. Physicians must be empowered to gain mastery in treating these disorders the same way they learn to treat ‘organic’ illness. A lack of personal accomplishment is a core feature of burnout; we must equip our doctors with the knowledge and skills to effectively treat these conditions.

- There are so many fantastic resources through the Rome Foundation to self-educate! Here are a few:

- The new book, Gut Feelings: Disorders of Gut-Brain (DGBI) Interaction and the Patient-Doctor Relationship, A Guide for Patients and Doctors, written by physician expert Douglas Drossman and patient turned patient-advocate, Johannah Ruddy. This book outlines the Rome Criteria for DGBI as well as history, tips, and tools for living with and treating DGBI: https://romedross.video/GutFeelingsWebsite

- A Grand Rounds Lecture at Mt. Sinai Hospital in NYC where Dr. Doug Drossman addresses chronic abdominal pain: https://romedross.video/GersonLecture

- A fantastic TED-like talk on patient stigmatization and communication skills: http://bit.ly/2HbpVDy

- A recent review paper Dr. Drossman and I wrote about stigma in patients with DGBI: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/nmo.14080 and a subsequent discussion we had about the topic: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O8PEE8ctAkg).

- There are so many fantastic resources through the Rome Foundation to self-educate! Here are a few:

- Excellent patient-physician communication. As cited in all of the resources shared above, research shows that a therapeutic patient-physician relationship is one of the best predictors of recovery in DGBI. These skills, which can be learned and developed, involve listening actively, identifying a patient’s agenda, empathizing, validating, setting realistic goals and expectations, providing reassurance, and empowering patients to take an active role in their own treatment. When patients feel empowered by their clinicians to become active participants in their treatment, this reduces the sense of sole responsibility (and the potential for failure) on behalf of the physician that can directly fuel burnout. An excellent patient-physician relationship is also cited as one of the most meaningful parts of a physician’s job, and an antidote to burnout in itself. Thus, optimizing communication and this relationship can reduce stigma benefitting patients AND help to heal doctors who might be suffering as well. A Rome Foundation working team just published in Gastroenterology a comprehensive review of patient-physician communication showing that effective communication skills are associated with improved patient and physician satisfaction, improved clinical outcomes, and reduction in costs. The article also provides tips and techniques for the clinician to apply in practice.

- Moving beyond the Biomedical Model to the Biopsychosocial Model. Ultimately, if we remain stuck in the legacy of Descartes’ Mind-Body dualism, we will surely miss out on the vast power of mind/body synergy in understanding illness and developing novel treatments. This pertains to DGBI as well as psychiatric disorders (and even burnout) that are also highly subject to stigma. Our ethos in training and practice must evolve to prepare us to treat what Dr. Douglas Drossman calls “illness without disease” – symptoms without a clear, observable cause. Doing so requires embracing the biopsychosocial (BPS) model of care, which recognizes that behind all states of health and disease are powerful, and inextricable connections among biological, psychological, and social factors. Psychological and social factors are not extraneous but rather just as essential as biology. Embracing BPS requires getting to know our patients in a holistic way, and explicitly from the centuries of dualism that pervade modern medicine.

Addressing stigma for patients with DGBI requires that we simultaneously address many of the drivers of clinician burnout that contribute to reductionism and invalidation for patients. Until our doctors are trained, compensated, and given the time and space to care adequately for patients with complex chronic diseases, stigma for BOTH DGBI (and other “functional” disorders) and burnout will continue. I am hopeful that we are already moving in the right direction.

Jordyn Feingold, MD, MSCR, MAPP

Jordyn Feingold is a resident physician in psychiatry at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. She is also a researcher and positive psychology practitioner & teacher. Her research and clinical interests involve working with patients with disorders of gut-brain interaction (DGBI) as well as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and other chronic diseases. She is also a champion of clinician well-being and is involved in research, curriculum development, teaching, and advocacy locally and nationally. Jordyn has developed and implemented evidence-based resilience trainings for physicians, including an online course open to all clinicians called Thrive-Rx.

Facebook: Jordyn H. Feingold @JordynHFeingold

Twitter: @JordynFeingold

Instagram: @ThePositiveMedicine

5826 Fayetteville Rd., Suite 201 Durham, NC 27713

5826 Fayetteville Rd., Suite 201 Durham, NC 27713  (919) 246-5611

(919) 246-5611