By: Meghan Huff PA-C and Douglas Drossman MD

The art of medicine has been losing ground as it moves further into the world of technological advances. With the increased use of imaging diagnostic studies and the rise of telemedicine, the number of patients receiving medical care without actually being seen is growing. Unfortunately, even within person visits, medical providers are often pressed for time as they struggle to meet patient quotas. These two elements combined have led to more and more patients having less physical contact with their providers. While physical exam is still taught in schools, one element of the physical exam is being woefully neglected, specifically the digital rectal exam (DRE). In the last several months I have had more than an occasional patient referred to me say that I was the first gastroenterologist to do a rectal exam for their constipation or pelvic floor problems.

Importance of the Rectal Exam

In a study we published in 2012 in The American Journal of Gastroenterology, Dr. Drossman along with expert gastroenterologists, Reuben Wong, Arnold Wald, Adil Bharucha and Satish Rao did a survey of over 650 clinicians to assess the utilization of the rectal exam, which at that time, was already diminishing1. While many providers may not see why they should do a rectal exam, and certainly not all providers should be, the benefits of the digital rectal exam far outweigh the momentary physical discomfort with the patient or possibly transient emotional awkwardness felt by the patient or clinician. The benefits of DRE include assessing overt or occult blood in the stool, pelvic floor dyssynergia, anal fissures, rectal prolapse, prostatic hypertrophy in men, and pelvic floor prolapse and rectocele in women2. A rectal exam is a major component of the physical exam and is essential for patients presenting with constipation, or any type of anorectal difficulty.

Constipation is a fairly common complaint in within Gastroenterology and primary care offices. Chronic constipation can lead to significant discomfort and have a negative impact on health related quality of life. Treatments for chronic constipation will vary based on the pathophysiology of the condition, which can vary. One component of chronic constipation is pelvic floor dyssynergia (PFD), occurring in more than 1/3 of patients presenting to gastroenterologists and some patients with PFD don’t even have constipation. It is important for this to be identified as it can be effectively treated with biofeedback as discussed below3.

Pelvic Floor Dyssynergia

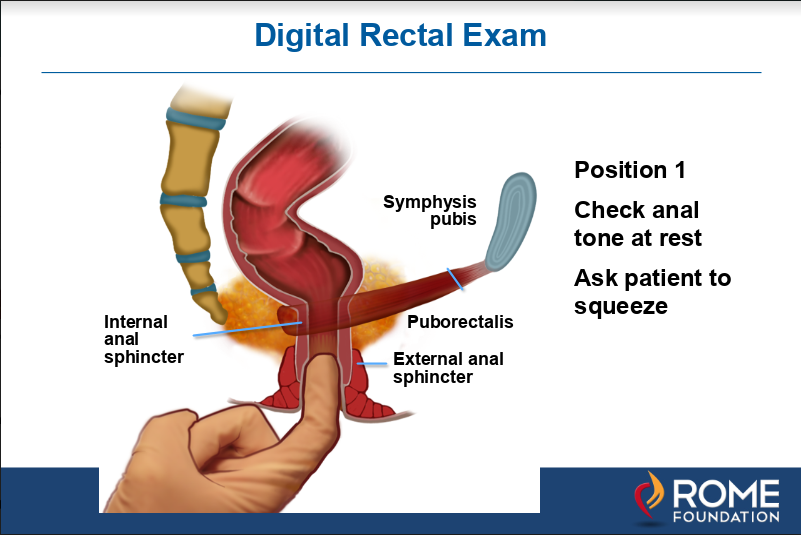

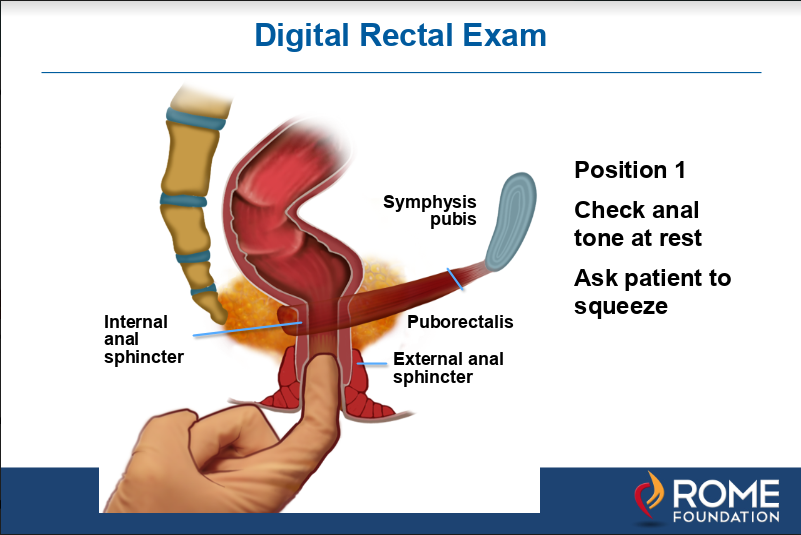

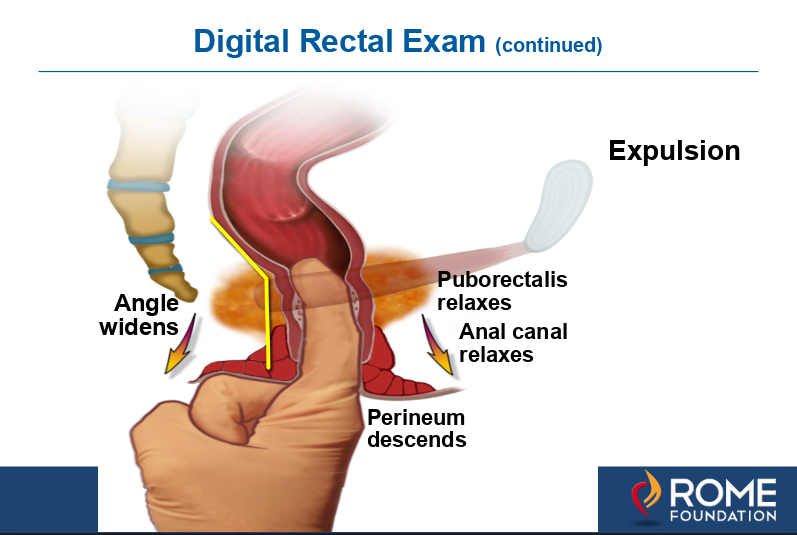

So, what is pelvic floor dyssynergia? The pelvic floor is made up of skeletal muscles that surround the pelvic bones and support internal organs, such as the bladder, from below. The main muscle, called the Levator Ani, is made up of three parts: the iliococcygeus muscle, the pubococcygeus muscle, and the puborectalis muscle. These muscles create tension to pull the rectum from being straight naturally into a right angle, thus creating a physical barrier that allows humans to be continent with control over when we defecate. During defecation the levator muscle group relaxes, the rectum straightens and stool can easily be evacuated. In patients with pelvic floor dyssynergia, the levator muscle group surrounding the rectum are pulled tight and they won’t relax, or may even tighten even when the patient is actively trying to defecate. This leads to straining against the angled rectum and when more severe can lead to pain, pelvic floor prolapse or the development of a rectocele. The diagnosis can be readily made during the rectal exam or confirmed with an anorectal motility study (See Figures). Once identified, PFD can be treated through biofeedback as well as training during the rectal exam.

PFD can be considered first with the medical history. The patient can be asked if they strain with normal or soft stool (straining in healthy persons occurs when the stool is hard or in pieces). In addition, patients with PFD squeeze their pelvic floor while those without PFD squeeze just their abdomen and relax their bottom when defecating. The rectal exam technique relates to the practitioner to having the patient relax the bottom and then bear down as if having a bowel movement. In patients with pelvic floor dyssynergia, when bear downing, these muscles may not relax or involuntarily tighten again. Providers who are proficient in performing digital rectal exams can not only detect this dyssynergic defecation, but they can also use the exam to instruct patients on how to relax the pelvic floor allowing for ease of defecation. Of note, if the provider never examines the patients and doesn’t ask the right questions, this diagnosis could be completely missed.

Levator Ani Syndrome

Another related condition is called Levator Ani Syndrome which occurs when the muscles of the pelvic floor are tense enough to cause rectal pain. If the pain is relatively brief (less than 20 minutes) it is called Proctalgia Fugax. However, when the pain lasts for longer periods of time it is called Levator Ani Syndrome. As with pelvic floor dyssynergia, this can be diagnosed by rectal exam; the practitioner assesses applies pressure to the levator on both the right and left sides of the rectum. Patients with levator ani syndrome will report pain with this increased pressure, which typically is more severe on the left side. Thankfully, the digital rectal exam can also be useful in treating levator ani syndrome through gentle rectal massage. Patients with Levator Ani Syndrome and/or Pelvic Floor Dyssynergia may also benefit from pelvic floor physical therapy and modified Kegel exercises. Specifically, asking the patient to find their pelvic floor muscles, contract them, relax, and then maintaining relaxation, push down. These exercises can be instructed on the visit with the DRE and then practiced at home, with a re-evaluation by DRE at the next visit.

Challenges to the Rectal Exam

Patients may feel uncomfortable or embarrassed by having a rectal exam, but most do not and if well prepared will readily accept this important procedure. Providers need to properly learn these techniques and when they are comfortable and competent with the exam; the patient is more accepting and proper diagnoses can be made. Patients should be assured that the exam will only last a couple of minutes. Patients are more willing to be examined if they feel that their provider is experienced in the exam. Medical schools, residencies and fellowships must continue to teach and encourage others to practice these vital hands-on skills, for the benefit of patients whose diagnosis may otherwise be missed.

Figure 1a. As shown above, in position 1 the finger is inserted into the anal canal to feel the strength or tone of the external sphincter by asking the patient to squeeze.

Figure 1b. Next the finger is inserted deeper to just above the puborectalis muscle which is felt posteriorly in the rectum as a ridge. This muscle will tighten and push toward the finger when the patient is asked to squeeze.

Figure 1c. Then expulsion is tested by asking the patient to relax the pelvic floor while pushing down from the abdomen to simulate defecation. When done properly the anorectal angle widens as the puborectalis relaxes. With dyssynergic defecation the angle does not widen or becomes more acute as the levator contracts. This is diagnostic for dyssynergic defecation and can be treated by pelvic floor training during the clinic visit or with biofeedback using a rectal probe device.

Reference List

- Wong RK, Drossman DA, Bharucha AE, Rao SS, Wald A, Morris CB, Oxentenko AS, Van Handel DM, Edwards H, Hu Y, Bangdiwala S. The digital rectal exam: A multicenter survey of physician and students’ perceptions and practice patterns. Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107:1157-1163.

- Talley NJ. How to do and interpret a rectal examination in gastroenterology. Am J Gastroenterol 2008;103:820-822.

- Rao SS, Valestin J, Brown CK, Zimmerman B, Schulze K. Long-term efficacy of biofeedback therapy for dyssynergic defecation: Randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2010;105:890-896.

5826 Fayetteville Rd., Suite 201 Durham, NC 27713

5826 Fayetteville Rd., Suite 201 Durham, NC 27713  (919) 246-5611

(919) 246-5611